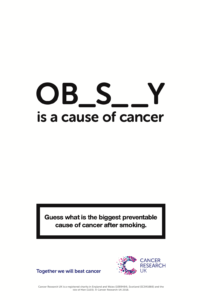

In March 2018, the charity Cancer Research UK (CRUK) launched a poster campaign in London that sought to raise awareness of epidemiological links between obesity and cancer. The posters consisted of various images accompanied by the text: “OBESITY: guess what is the biggest preventable cause of cancer after smoking”. The text was in black and white, suggesting that, while shocking, these assertions are simple, straightforward statements of scientific fact.

Yet they generated a heated debate on social media: campaigners and public figures said they would stop donating to CRUK – one of the largest charities in the UK – on account of its “fat-shaming” campaign, while Professor Linda Bauld of CRUK countered that it was, “not about fat shaming” but, “based on scientific evidence and designed to give important information to the public”. Others rallied to defend CRUK’s positive track record of fund-raising, and criticized those offended for “interpreting the facts emotionally”.

The controversy can be read as an example of how science is entangled with particular understandings of health, politics, and effective public policy in the UK. Weeks after these posters appeared in bus shelters, the British government introduced a ‘sugar tax’ on fizzy drinks, and the following year London Mayor Sadiq Khan announced a ban on the advertisement of products high in fat, salt and sugar on London public transport. Both measures have as their stated aim the need to tackle the “ticking time bomb of child obesity”, yet both have been criticized for failing to take into consideration the wider societal drivers of ‘obesity’, and so for wrongly identifying individual eating habits as both the problem and the solution.

The field of science and technology studies (STS) seeks to understand controversies such as these, by inquiring about the taken-for-granted assumptions at the heart of both scientific claims and challenges to them. Such questions can help us understand how we come to care about and define a societal problem called ‘obesity’, and the implications of doing so. For example, what does being ‘healthy’ in modern times mean, and how are ‘the healthy’ and ‘the unhealthy’ identified? What roles are ascribed to the state and the citizen through the concept of ‘obesity’ as imagined by campaigns such as CRUK’s, and with what implications for social justice? And how and why do these roles and meanings change over time, gaining purchase (or not) in the minds of British citizens?

Applying analytic concepts from STS to the CRUK controversy can reveal how these questions came to be hidden, and were then rediscovered in the row over these posters, and whose voices have become excluded in the process.

On the one hand, CRUK defended its posters through two methods. Firstly, it appealed to the idea that epidemiological science and societal conversations – or ‘facts’ and ‘emotions’ – are discrete phenomena that operate in separate domains. Such assertions are a form of boundary work (Gieryn 1983): a rhetoric in which people or institutions seek credibility and authority by explicitly demarcating their claims from the world of values, social norms and politics. This claim that scientific facts are uncontaminated by values and politics leads to the second method of defense: the deficit approach (Jasanoff and Wynne 1998) to knowledge and public policy. This refers to the conviction that controversies are created by a deficit of facts, and can therefore be solved by sending more (supposedly neutral) facts into the public domain.

On the other hand, those who challenged CRUK did so by rejecting the suggestion that the posters represented neutral scientific facts, by highlighting and questioning the norms and values embedded within them. Many contended that the posters reproduced moralizing discourses of fatness as shameful and sinful, and questioned what the term ‘obesity’ is actually standing in for, and how it suggests and apportions blame. For example, equating ‘obesity’ with smoking cigarettes – a recognized symbol for self-inflicted harm – reinforces the supposed incontrovertibility of both the boundary between right and wrong, and the agreed-upon terms on which this particular boundary is founded.

Meanwhile, emphasizing the “preventability” of the issue resonates with the political discourses of both right and left. The right, decrying a wasteful, ‘nannying’ national health service, is likely to approve the delegation of responsibility to the individual for her own health; while the left welcomes the recognition of environmental and structural forces, such as corporate greed being held responsible for junk food advertising and inadequate education and welfare. For both sides, such discourses work to construct ‘obesity’ as a byword for the moral individual and societal failings of modern British society.

In a world in which science frequently fails to have the authority post-Enlightenment thinkers desired for it, at least two lessons can be learned from the inability of CRUK’s posters to resonate with certain groups of society. Firstly, scientific institutions need to recognize that facts do not acquire authority among publics simply by virtue of being neutral representations of the world, but because of the ways in which they are not. Hence, science must ask more questions about the social and political contexts in which it becomes an authoritative representation of the world it describes, and whose voices are included and excluded in this process. To this end, many STS scholars have urged scientists to be more open and humble about the norms and values embedded in their work, so that they can be debated, and scientific knowledge can be made more meaningful to the constituencies to which it matters (Jasanoff and Simmet 2019; Wynne 2006). Secondly, democratic publics and governments must acknowledge the values embedded in science, and their capacity to shape them, rather than expecting science to simplify complex societal issues and quench controversies through the delivery of neutral facts.

Keywords: public health, obesity, STS, science

References

- Gieryn, Thomas. 1983. “Boundary-Work and the Demarcation of Science from Non-Science: Strains and Interests in Professional Ideologies of Scientists.” American Sociological Review 48 (6): 781–95.

- Jasanoff, Sheila, and Brian Wynne. 1998. “Science and Decisionmaking.” In Human Choice and Climate Change, edited by Steve Rayner and Elizabeth L. Malone. Columbus, Ohio: Battelle Press.

- Jasanoff, Sheila, and Hilton R. Simmet. 2017. “No funeral bells: Public reason in a ‘post-truth’age.” Social studies of science 47 (5): 751-770.

- Wynne, Brian. 2006. “Public Engagement as a Means of Restoring Public Trust in Science – Hitting the Notes, but Missing the Music?” Public Health Genomics 9 (3): 211–20.

Further Readings:

Epstein, Steven. 1998. Impure Science: AIDS, Activism, and the Politics of Knowledge. Reprint. Medicine and Society 7. Berkeley, Calif.: Univ. of California Press.

Felt et al. (2014) ‘Timescapes of obesity: Coming to terms with a complex bio-medical phenomenon’. Health 18(6): 646-664

Jasanoff, Sheila (2017) ‘Back from the brink: Truth and Trust in the Public Sphere’ Issues in Science and Technology, 33: 4

Kirkland, Anna. 2008. “Think of the Hippopotamus: Rights Consciousness in the Fat Acceptance Movement.” Law & Society Review 42 (2): 397–432.

———. 2011. “The Environmental Account of Obesity: A Case for Feminist Skepticism.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 36 (2): 463–485.

Lupton, Deborah. 2013. Fat. Short Cuts. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge.

McPhail, Deborah. 2017. Contours of the Nation: making “Obesity” and imagining “Canada,” 1945-1970. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.