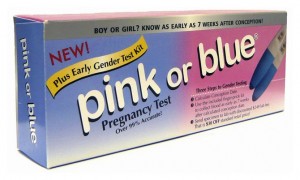

Early gender pregnancy tests have hit the market in the United States. Available direct-to-consumer at online pharmacies and maternity stores, medical genetic tests developed to select for sex in pregnancies with a strong risk of sex-linked hereditary disease are now being marketed as a way to decide whether to buy in pink or in blue as early as the 7th week of pregnancy. Moreover, a new study in the Journal of the American Medical Association suggests that fetal DNA tests, which detect y-chromosomes in a pregnant woman’s blood, are 95% accurate. This offers a reliable method of sex-determination months earlier than standard ultrasound exams, which typically occur at 18-22 weeks.

Some articles recently in the news have commented on how these tests might be used for family balancing or for discriminatory abortions. Other articles draw out how the tests are only available in the United States through direct-to-consumer options. This is an area ripe for ethical discussion, but that is not the only point of entry for an STS analysis, as the following scholars point out:

Much of the debate surrounding these tests has focused on their potential use for gender selection through abortion, and given the history of their development as tools for just this purpose in a medical context, such concerns make sense. Since its development through amniocentesis and later pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD), fetal genetic testing has been closely linked to selection against unfavorable traits. Early gender tests fit within two larger trends that have transformed modern pregnancy: earlier and stronger identification with the fetus through technology; and an increasing illusion of control about the outcome of pregnancy. Early fetal gender tests offer a new way to animate early pregnancy a gestational period, where the NIH estimates that 50% of fertilized embryos naturally end in spontaneous abortion. An embryo becomes [labelled as] a little boy or girl. Excited parents can begin to decorate, pick names, and imagine a future full of gender appropriate activities, thus lending a sense of stability to a fragile period of pregnancy and magnifying its potential loss. These tests, through their marketing and even in the framing of the ethical debates surrounding their use, offer an illusion of control in gender selection. Any medical geneticist working on gender is quick to point out that even determining sex is a fuzzy thing. Is it genetic, in the sense the tests offer? Does a y-chromosome equal a male baby? Yes and no. The presence and experience of the intersexed already shows the limits of a male/female gender binary. Aside from medical debates, sex and gender are fundamentally social experiences, shifting and changing through our life course. By paying attention to early fetal gender tests within the larger, ever-shifting landscape of pregnancy and pre-natal choice and responsibility, we can expand the scope of ethical debate from a focus on abortion and individual choice to the social pressures put on expectant families through an illusion of control offered by new technologies.

Lindsay Smith is a Postdoctoral Fellow at UCLA’s Center for Society and Genetics.

Shobita Parthasarathy

Much of the media coverage has focused on the technology’s potential benefits for early detection of sex-linked diseases, and the potential dangers for sex selection particularly in countries that have shown a preference for male births. Thus far, this discussion has missed the opportunity to reflect on how this technology represents the changing landscape of health care. Specifically, it is one of a growing number of medical tests that are now available online or at the local pharmacy, outside the care of a medical professional. Some of these tests provide information about an user’s current biochemistry, while others predict the user’s risk of contracting illness in the future. Many applaud this transformation, arguing that it empowers users to choose how and when to access the healthcare domain (provided she can pay for it). But the cost of this empowerment is that the “consumer” must bear the sole responsibility of using the test correctly and interpreting the information that it generates. Furthermore, it erodes the ethic of care in the medical arena, changing the relationship with the health care professional fundamentally. Before this transformation proceeds much further, we need to initiate a broad discussion about the implications of this sharp turn towards consumer medicine and then consider how we can mitigate its drawbacks.

Shobita Parthasarathy is Associate Professor of Public Policy at University of Michigan, and the author of Building Genetic Medicine: Breast Cancer, Technology, and the Comparative Politics of Health Care (MIT Press, 2007).