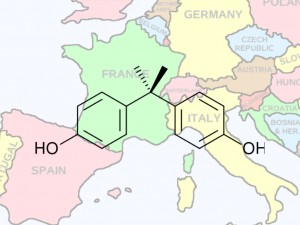

On June 1, 2011, all baby bottles containing Bisphenol A (BPA) were removed from stores everywhere in the European Union (EU) following the very first international ban on the substance. This ban was a response to many differences in regulation of BPA among Member States. The European Commission press release for the occasion drew attention to these discrepancies: “In 2010, France and Denmark had taken national measures to restrict the use of Bisphenol A. France focussed on baby bottles only, while Denmark targeted also other food contact materials intended for children.”

If the European BPA decision intended to correct for differences in Member State policies about chemicals, this harmonization was short-lived. Five months later, in October, the French National Assembly banned the use of BPA for any type of food packaging, surpassing both the European ban on the use of BPA for baby bottles, and the Danish ban on food materials intended for children. That decision was justified by a report prepared in the context of the REACH Regulation (1), by the French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health Safety (ANSES), whose recommendations challenged the conclusion of the European Food Safety Authority that the substance was safe for food contact applications. The ANSES report showed that the ingestion of BPA produces “‘recognized’ [harmful] effects in animals and other ‘suspected’ effects in humans (on reproduction, metabolism and cardiovascular diseases)” and recommended reducing population exposure to BPA (2). By following ANSES recommendations, French authorities appear to go against European-wide policies like REACH that are designed to harmonize chemical regulation among Member States so as to offer equal protection to all European citizens. Instead of supporting harmonization, the French apparently opted for subsidiarity, insisting on the independence of French expertise (3). A closer look shows, on the contrary, that ANSES’ recommendations on BPA, as that of other national agencies on different chemicals, feed the expertise necessary for European decisions to be made. The lens of chemical regulation enables STS researchers to analyze relations among nations, taking into account the complex linkages among the local, regional, and global levels where chemicals -and their risk assessments- circulate.

Because REACH work routines are not in place yet, ANSES benefits from a good deal of discretionary power in the European procedures: the decision to study BPA further in spite of the European decision on baby bottles, the literature review, the selection of strategic data, the pitch and the rationale of the case are largely choices made by ANSES. On their website, ANSES confirms “the health effects of BPA for pregnant women in terms of potential risks to the unborn child” (4). The ANSES study, they add, “was carried out as part of a multidisciplinary, adversarial collective expert appraisal,” with a “working group specifically focusing on endocrine disrupters.” The specificity of the French agency’s expertise on BPA partly lies in its ability to put forward their strategic research orientation on endocrine disruptors: BPA had been for several years part of an ambitious program that included “mandates on risk assessment, scientific monitoring and reference activities for endocrine disruptors” (5). This program is a major orientation of the agency, as endocrine disruptors are seen as political issue in France. Working on BPA, using the knowledge produced with this program and having the national restriction in baby bottles adopted at the European level suggest that an agency’s discretion can encourage European-wide restrictions. The novelty of REACH provides a valuable window of opportunity to the French agency to implement practices of subsidiarity, of what the procedures should be, based on the national agenda and ANSES’ ongoing research programs.

The BPA case is an example of producing European regulatory science by maintaining local control of expert judgment. EU institutions are often accused of lacking democratic accountability and legitimacy compared to Member States. With BPA, the practices of subsidiarity previously described show that the alleged democratic deficit is not systemic: national decisions can be used at the European level. It was this logic that led to the European ban of BPA in baby bottles to begin with. In a way, the discrepancies of expertise between Member States eventually lead to harmonization: European regulatory science, for instance in the REACH case, is in fact produced at the level of national health safety agencies that manage to create their own vision of doing expertise in the EU.

Keywords: regulatory science; Europeanization; chemical regulation

References:

- The Registration, Evaluation and Authorisation of Chemicals (REACH) is a European-wide regulation that was adopted in 2006 and that addresses the production and importation of chemical substances in the European Union.

- ANSES. “Effets sanitaires du bisphénol A, Rapport d’expertise collective,” September 2011.

- The subsidiarity principle is based on the idea that decisions must be taken as closely as possible to the citizen: the European Union should not undertake action, except on matters for which it alone is responsible, unless EU action is more effective than action taken at national, regional or local level.

- ANSES. “Opinion of the French Agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health & Safety on the assessment of the risks associated with bisphenol A for human health, and on toxicological data and data on the use of bisphenols S, F, M, B, AP, AF and BADGE,” 2013.

- ANSES. Presentation of the work of ANSES on endocrine disruptors, 2013.

Suggested further reading:

- Brickman, R., S. Jasanoff, and T. Ilgen. Controlling Chemicals: The Politics of Regulation in Europe and the U.S. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1985.

- Demortain D. Scientists and the Regulation of Risk. Standardising Control. Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing, 2011.